By Emil Sanamyan

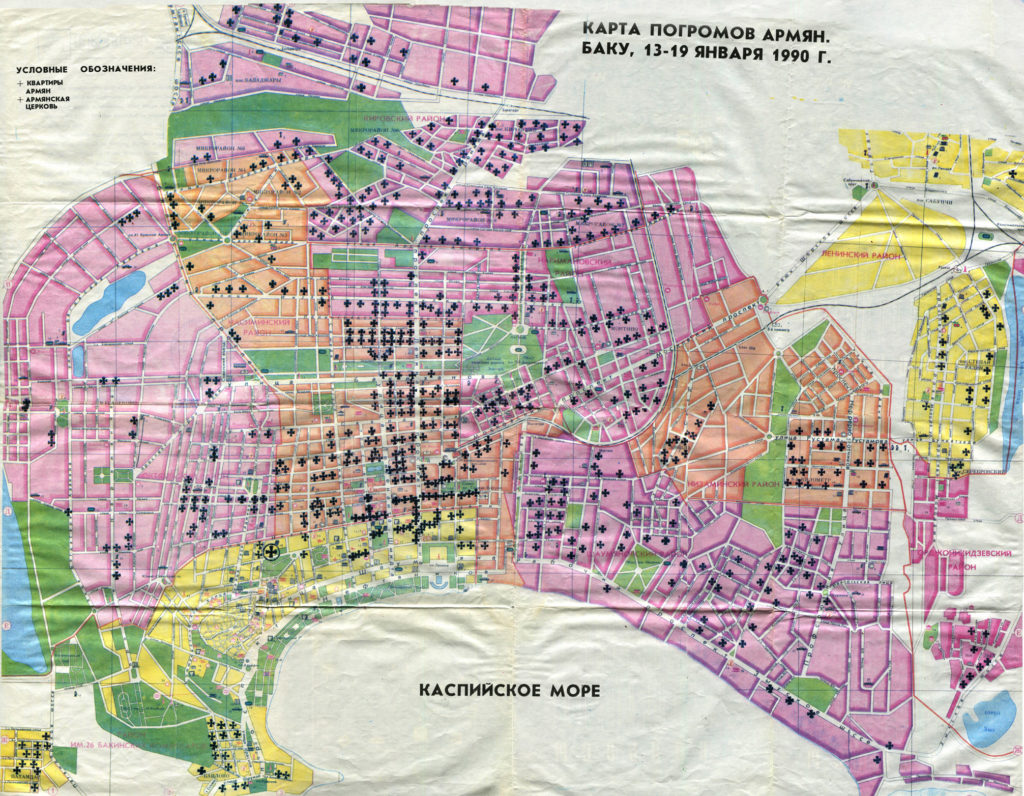

Episodes of mass violence, such as the Armenian pogroms in Baku in January 1990 and subsequent introduction of Soviet forces resulting in additional loss of life, are often viewed as events in themselves. From the Armenian perspective, the Baku pogroms were just another manifestation of anti-Armenian hatred in Azerbaijan, from Azerbaijani – it is often described as a conspiracy to quash local nationalist aspirations.

Putting these events in the context of the developing logic of the Karabakh conflict and growing crisis throughout the Soviet Union helps explain the events’ timing and some of the motives involved.

Thus, the initial appeals from Nagorno Karabakh Autonomy for its reassignment from Azerbaijan to Armenia were immediately followed by a violent reaction against Armenians in Karabakh, Sumgait and elsewhere. Following the violence of 1988, 1989 was a mostly peaceful year with relatively few conflict-related deaths reported. But conflict began to heat up again, after Karabakh Armenian leaders refused Kremlin’s offers to drop demands for unification with Armenia in exchange for upgrading NKAO’s status to an autonomous republic within then still Soviet Azerbaijan.

Most significantly, 1988 saw a massive population exchange between the two republics triggered by violent attacks that slowed down but continued in 1989. This made continued existence of an Armenian autonomy, whether an oblast’ or a republic, within Azerbaijan increasingly unrealistic. Since prior to the conflict there were more Armenians in Azerbaijan than Azerbaijanis in Armenia, by the end of 1989 the flight of Azerbaijanis was nearly complete (one exception was the Nuvadi area near Meghri), whereas an estimated several tens of thousands of Armenians still remained in Baku and in villages to the immediate north of NKAO that, counting on Armenia’s support, prepared for self-defense.

On November 28, 1989, the Soviet government cancelled the direct administration in Nagorno Karabakh in effect since January 1989, returning the Oblast under Azerbaijan’s administration. In response, on December 1, 1989 the Supreme Council (Parliament) of Armenia issued a union declaration with NKAO.

Also Read: Russia’s Kommersant Publishes Map of Armenia-Azerbaijan Transport Corridors

The Soviet Azerbaijani leadership prepared for a crackdown in and around Nagorno Karabakh. In December 1989, the number of Soviet security forces in the area were increasing from nine to fifteen thousand further backed by the regular army units. On January 9, 1990 Karabakh Armenian activists rallied to stop Soviet Azerbaijani leader Abdurrahman Vezirov accompanied by Moscow officials from arriving in Stepanakert. Resulting clashes with Soviet security forces left three activists dead.

At the same time, armed volunteers began to arrive in Karabakh from Armenia, particularly to the village of Getashen in Khanlar district, north of NKAO. In parallel, Armenian militias from Yerevan attacked an Azerbaijani enclave of Kerki, which sat on Armenia’s main highway just north of Nakhichevan, and after a week-long siege expelled its population.

Starting on January 11, Azerbaijani militias associated with the Azerbaijani Popular Front attacked Armenian villages in Khanlar and Shaumyan districts, seeking to force their residents to flee to Armenia. The shooting in the area continued for days with some seven Azerbaijani attackers reportedly killed.

As in February 1988, when after the failure of the initial Azerbaijani show of force in Karabakh, the violence was redirected towards Armenians in Sumgait, this time the perceived setback in Karabakh was quickly followed by attacks on remaining Armenians in Baku, where Popular Front demanded that Azerbaijani refugees should be housed in “abandoned” Armenian homes. In the following days, more than 90 Armenians were killed in Baku in mob attacks. Others were protected by their Azerbaijani friends and neighbors, only to be evacuated by the Soviet military.

As pogroms escalated, on January 14 Kremlin officials led by Yevgeni Primakov were dispatched to Baku. Soviet Azerbaijani leaders refused to introduce emergency rule, even as such rule was introduced in NKAO, where violence was on the lesser scale. On January 16, Soviet defense and interior ministers arrived in Getashen and pledged to protect the Armenians in the area (they kept their pledge until the spring of 1991, when these villages were ethnically cleansed with the help of the Soviet forces).

As violence in Baku continued to spread, on the night of January 19-20 Soviet military was ordered into the city over objections from Vezirov, who was effectively removed. As Popular Front activists attempted to stop them, more than 100 Azerbaijani civilians and activists died in the clashes.

Baku pogroms thus became part of the Azerbaijani nationalist backlash to Armenia’s union declaration with Karabakh and the Armenian resistance in Karabakh. Three decades on, no official investigation into the pogroms has been conducted and no one was held responsible.