Guillaume de Chazournes

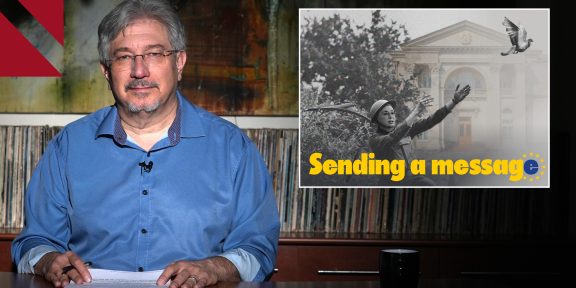

On Sunday, June 8, I discover a book called “Memory of my Memory” by Gérard Chaliand, and without knowing what it is about, I borrow it. A few minutes later, I go to 11 Teryan Street to observe Armenian activists from the civic group “Let’s Save the Afrikyan Club Building,” who are trying to preserve this building constructed in the late nineteenth century. Opening the first pages of the book, I realize that it addresses the Armenian Genocide and the fundamental issue of memory. Pages turn, and the more I read, the more I pause to observe what’s happening in front of me. The memory of the past that Chaliand is trying to preserve in these pages … the memory of the past that these activists are trying to save by protecting these walls. Words of the past and acts of the present. A link is created, a natural connection like an imaginary dialogue between Chaliand and activists of all ages who are fighting for the preservation of Yerevan’s architectural heritage.

“My ramparts are just old boundary walls of a city without prestige. I am defending neither proud Byzantium, nor thrice holy Jerusalem. I’m defending Hadjin, capital of my desire to live.” Gérard Chaliand

For several years now, many Armenian citizens have been mobilizing to preserve the beauty of their city walls, the stone memory of their past. Not to exalt a lost golden age, but to proclaim their desire to live between the walls that reflect their collective identity, at the crossroads of a tormented past and a political, social and geopolitically uncertain future. Destroying these walls is to destroy memory and part of the Armenian identity.

Confronted with politicians who seem incapable of understanding the importance of the role of memory and its resulting responsibilities, these young activists have decided to insure, on their own, the protection of their ancestors’ memory in order to create a better future.

“Churches with demolished walls, gaping porticos, erased frescoes, and defaced reliefs. But their bells ring out their toll of agony for you. Ring the bells of the Cathedral of Ani, those of Akhtamar and those of free Armenia. Song full of memory that time, full of forgetfulness, cannot shake.” Gérard Chaliand

These young people do not want to yield to the tragedy of Armenian history, that of a permanent destruction and a fragile and uncertain survival. Refusing the demolition of this building, designed by architect Vasili Mirzoyan at the end of the 19th century, is also refusing to let the last vestiges of a particular type of Armenian architecture disappear. For the walls and contours of the Afrikyans Club Building are, according to specialists, unique to Armenia and Yerevan. Sunday night, in the sweetness of a late spring, the sound of sandpaper clearing off white numbers marked on the stones replacing the sound of church bells. The sound of little hands caressing and protecting the facade became, just for an evening, the song of memory refusing to fade into oblivion.

Destroying a historic monument is like sacking and burning a library and its countless shelves of human stories. The Afrikyans Club Building’s facade is a veil of beauty behind which stories were lived, doors were opened, families torn apart and eventually reconciled, and meals were shared. The Afrikyans Club Building’s history is precisely one of meetings and sharing. In 1920, the building was nationalized and became the Yerevan City Club, where cultural events and meetings between Armenian intellectuals and artists were organized for many years.

Today, it is still the place where life resists, where families claim their legitimate right to live within the walls of their ancestors, within their memory. The history of the Afrikyans family that occupies the premises must be told, recounted, shouted, because it embodies a part of Armenia’s past. Their ancestors were the ones who established the first water pumping and cleaning system in Yerevan at the end of the nineteenth century. Owners of several companies, they participated in Armenia’s development while devoting a portion of their wealth to charitable works, which earned them recognition from Armenians. Throughout the twentieth century and until today, the family has continued to use the space. These walls have been benevolent witnesses to what they have seen and experienced, like time watchmen, withstanding and accompanying men in their joys and sorrows.

To destroy this facade and any Armenian architectural heritage is to destroy the history of this family, the history of Armenia. It is an insult to the memory of those who came before us. For they have left a mark, at once an imprint of history and a pathway to the future.

The famous Polish journalist Ryszard Kapuscinski wrote: “Scorned by a government, reduced to an object, degraded, the people seek a refuge, a place where they can burrow, retreat, to preserve who they are. It is essential if they want to keep their personality, their identity, or even simply their banality. But an entire people cannot emigrate. So instead of traveling in space, the people travel in time.”

Young Armenians are living through the difficulties of their present and are sometimes forced to travel through their past to better reflect upon their future. And the struggle for the preservation of their architecture shows it. They know the importance of a clear dialogue with their past.

Armenia does not deserve to be left to authorities who are blinded by the present and its illusions. Those in power who deny and forget the hardships of the past to care only about their current wealth and privileges. Those who are decaying in their solitary “I” at the expense of the united “we.” In recent years, these irresponsible politicians have destroyed 90% of the historical heritage of Yerevan. Even though they classified the building in 2004 as historic heritage of the city, thus preventing its destruction, they do not hesitate today to destroy it and replace it with a hotel, ensuring greater profitability. Their cynicism is sickening.

This government only swears by its obsession to transform the center of Yerevan into a big Western store front, sweeping the economic and social challenges of today’s Armenia under the rug. And to calm things down, they put forward their project entitled “Old Yerevan,” supposedly aimed at reconstructing these historical buildings in another part of town. Ten years after the official announcement of this program, no building has yet been rebuilt.

“The scale of a disaster is always measured too late.” Gérard Chaliand

Once this facade is destroyed, it can’t be undone. It is therefore necessary to prevent its destruction. Victor Schoelcher, a French politician who wrote the bill abolishing slavery in France, said, “It is in the essence of an unjust power to always be shaken by the feeling of what is right.” The battle of Armenian activists is one of justice and present tribute to the past. It is legitimate and must now gain the support of the population. For beyond the facade, it is all Yerevan architectural heritage that is threatened.

“More than ever, moral force is critical. When the issue is vital for you and not for the opponent, you have often already won.” Gérard Chaliand

The issue is not vital in the first and individualistic sense of the term. It is, however, vital to preserve the past and the Armenian collective imagination. It is vital to preserve memory, the only guarantee of a more lucid and more decided present. In this way, the mobilizing activists are already winning the battle of Yerevan’s memory.

Do not resign, but resist. Do not forget, but claim. A legacy, a memory.

The memory of their memories.