By Lilit Abovyan

With the new government’s focus on identifying and holding accountable those engaged in corrupt practices, it is important to understand the fundamental links between corruption and economic growth — in all countries, not just Armenia.

Responding to a survey conducted by Transparency International Armenia, one out of every 5 respondents stated that they have paid a bribe to at least one governmental institution. How important is the correlation between corruption and economic growth? Is corruption part of culture? Is it possible to curb corruption?

According to German economist, Professor Johann Lambsdorff, data suggests that an increase in corruption by one point on a scale from 10 (highly clean) to 0 (highly corrupt) lowers productivity by 4 percent of GDP and decreases net annual capital inflows by 0.5 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

Lambsdorff’s study used data from the 2001 Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index (TI CPI). He suggests that breaking up corruption into different subcomponents reveals that the impact on productivity largely results from a positive association of corruption and a low bureaucratic quality.

Thus, the lower the level of corruption perception in any country, the higher the prosperity. And vice versa.

The table presents the per capita GDP for those countries that take the first five and the last five positions in the 2017 TI CPI. The annual average per capita GDP of the five countries with the lowest level of corruption perception index is 57,472 USD. While the average per capita GDP of the five countries with the highest level of corruption does not pass 1,000 USD.

According to a 2015-2016 survey conducted by the Transparency International Anti-Corruption Center, in Armenia, 24% of the respondents have paid a bribe to at least one governmental institution.

Transparency International’s 2015 country report describes the political landscape in Armenia as “dominated by a powerful president, the ruling party and numerous sitting members of parliament with strong connections to the private sector. The executive is largely unaccountable to other state actors and citizens due to weak systems of checks and balances.”

The report characterizes Armenia’s democratic transformation as “both incomplete and inadequate.”

Armenia and Corruption Perception

Armenia’s Corruption Perception Index (CPI) has not changed significantly since 2012.

In 2015, the Armenian government established the Anti-Corruption Council as a result of structural changes that took place in the Council in 2004.

Nonetheless, public trust towards the government’s fight against corruption has not increased.

According to the TI 2015 – 2016 report, the steps taken by the Armenian government to handle the fight against corruption are rated fairly well or very well only by 14% of the respondents (in 2013 it was 21%), whereas 65% of the respondents rated those steps as very bad or fairly bad.

Respondents believe that those who represent government institutions are the ones most heavily involved in corruption, with nearly half of respondents perceiving that all or most of them are involved in corruption. Forty four percent believe the president and his staff are involved in corruption and 43% believe tax officials are involved.

Fifty two percent of respondents in Armenia think that the ordinary person cannot do anything to help combat corruption. And 77% of respondents stated that reporting corruption is not socially acceptable.

The report concludes that as in 2013, in 2015-2016 as well, the issue is the lack of public willi to fight corruption.

Anti-Corruption Success Stories

What’s the role of institutional mechanisms in the fight against corruption? Let’s take a look at successful cases of anti-corruption experiences from several countries.

SINGAPORE

When Singapore’s Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew initiated his anti-corruption reforms in the 1960s, his message was the following: “If you want to win corruption, be prepared to send your friends and relatives to prisons.”

To eliminate corruption, Lee Kuan Yew deemed it necessary to eliminate the deeply rooted power-money-corruption cycle. A special anti-corruption program was created which in addition to others, planned to take the following measures:

– Ensure transparency between various levels of staff in the government.

– Ensure regular turnover of officials to avoid the formation of corruption chains.

– Conduct surprise checks.

– Deepen cooperation with citizens and organizations to fight against the bureaucratic red tape.

– Increase the salaries of officials.

– Give rise to independent, free and fair media that will investigate and reveal corruption cases.

GEORGIA

Georgia’s successful anti-corruption campaign following the 2003 Rose Revolution was aimed at improving public services.

The World Bank notes that Georgia’s case can serve as an example and be implemented in many countries. In particular, it highlights the critical presence of political will, the hiring of new staff, and the introduction of non-traditional methods. For example, it was noteworthy that in order to eradicate corruption in State Motor Inspection, President Mikheil Saakashvili fired all 15,000 employees and began to hire new ones.

The World Bank notes that Georgia’s experience breaks the stereotype that corruption is part of culture.

These changes decreased Georgia’s citizens’ perception of corruption. If in 2003 Georgia ranked 124 among 133 countries in the CPI, in 2006 its ranking was lowered to 99 among 163 countries.

World Bank’s Six Steps to Fighting Corruption

Studying the ways in which corruption affects the country’s social and institutional systems, the World Bank offers six basic approaches to fighting corruption.

1. Paying civil servants well

If public sector wages are too low, employees may find themselves under pressure to supplement their incomes in “unofficial” ways. A 2001 study shows that in less developed countries, there is an inverse relationship between the level of public sector wages and the incidence of corruption.

2. Creating transparency and openness in government spending

The more open and transparent the process, the less opportunity it will provide for malfeasance and abuse.

3. Cutting red tape

The high correlation between the incidence of corruption and the extent of bureaucratic red tape as captured, for instance, by the Doing Business indicators suggests the desirability of eliminating as many needless regulations while safeguarding the essential regulatory functions of the state.

4. Replacing regressive and distorting subsidies with targeted cash transfer

Subsidies are another example of how government policy can distort incentives and create opportunities for corruption.

5. Establishing international conventions

Because in a globalized economy corruption increasingly has a cross-border dimension, the international legal framework for corruption control is a key element among the options open to governments.

6. Deploying smart technology

Just as government-induced distortions provide many opportunities for corruption, it is also the case that frequent, direct contact between government officials and citizens can open the way for illicit transactions.

***

Following the 2018 Velvet Revolution, Armenia’s new government, led by Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, has launched a rigorous fight against corruption. High-profile corruption scandals and arrests have become part of the daily news flow.

In the long-run, will Armenia succeed in its fight against corruption? To what extent will political will be paired with strong institutional mechanisms to combat corruption?

Despite the amount of work that remains, it is clear that Armenia’s current anti-corruption path will significantly impact its position in the next Corruption Perceptions Report.

Lilit Abovyan is an economist and researcher at the Civilitas Foundation.

Translated by Zara Poghosyan

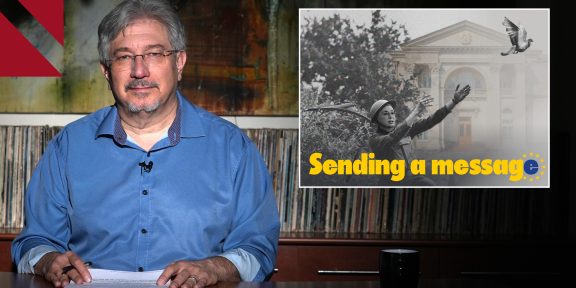

Photo: The houses of government officials in Monument District of Yerevan

Read the article in Armenian