By Syuzanna Petrosyan

On April 2, Armenians will go to the polls to elect a new parliament. But this parliament will be unlike any other since independence. Under the new constitution, adopted by a referendum on May 2015, Armenia will be incrementally transformed to a parliamentary state by the end of the current president’s second term — in April 2018. Until then, Armenia is still a semi-presidential state.

Armenia’s governing system has evolved from a strong presidential system (per the 1995 constitution) to a semi-presidential (per the 2005 constitution) and eventually to a full parliamentary (per the 2015 constitution, and to enter into full force in April 2018). This means that the current president will maintain his full authority, as granted by the 2005 constitution. This authority pertains mostly to matters of defense, security and foreign policy, with social-economic issues delegated to the prime minister. That is why it’s considered to be semi-presidential, since the parliament – and the prime minister – are mandated with significant domestic powers. But since one party has dominated and controlled all branches of government at all times, that divided authority has never been put to the test or allowed to prove itself.

The day the new parliament convenes at the end of May, this year, most of the new constitution’s provisions will enter into force – including those on establishing coalitions. The prime minister will be selected by a simple majority vote, although his authority will remain limited until the current president’s term ends in May 2018. At that time, the prime minister – the same one or a new one – will be bestowed with full executive power and become head of state, while a president, whose position will be mostly ceremonial and non- partisan, will be elected by three-fifths of the members of parliament. That very day, the new constitution will be in force, down to the last letter, and Armenia will be declared a fully parliamentary state.

Once that is achieved, the power center will shift to the parliament and the balance of forces and their depth of allegiances will determine the stability, the effectiveness and the longevity of the prime minister and the government. While the prime minister will combine the power, the influence and authority that was previously divided between the president and the prime minister, he (or she) could be subjected within a year of appointment to a vote of confidence by only one third of the 101 member body and to dismissal by a simple majority.

It is in this context that the current contest between five political parties and four alliances becomes critical. Those parties which receive a minimum of five percent of the vote and those multi-party alliances which receive seven percent of all votes cast pass the threshold set by the electoral law and enter parliament.

The Communists and Liberal Democrats are the weakest and may not pass the required five percent threshold. The Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Dashnaktsutyun) and first president Levon Ter-Petrossian’s Armenian National Congress, in alliance with Stepan Demirchyan’s Popular Party of Armenia, are clearly favored by the ruling party to enter the parliament. In the case of the Dashnaktsutyun, they are a possible coalition partner with the ruling Republican Party. In the case of the Ter Petrossian Congress, they would be a possible collaborator on Nagorno Karabakh conflict resolution. The Armenian Renaissance Party, formerly Orinats Yerkir (Rule of Law), led by former Parliament speaker Artur Baghdasaryan, has a steady electorate and most likely will enter parliament with a comfortable margin. The Ohanyan-Raffi-Oskanian and Elq alliances are on the rise and their numbers could be crucial in the game of post-election coalition formation.

The ruling Republican party, mostly because of its financial and administrative resources, and the Tsarukyan Alliance, because of Gagik Tsarukyan’s charitable gifts, popularity, and financial resources, are viewed as the two entities sure to emerge as the leading parties. One of them will get a plurality, but hardly a majority to be able to form a government on its own.

And herein lies the danger for the ruling party, and the hope for the electorate. This might be the opportunity for the electorate to change the ruling party through the ballot box for the first time since independence.

Under the new constitution, a maximum of three parties or alliances can get together to form a government, if the sum of their numbers exceeds fifty percent. Once that magic fifty plus number is achieved among two or three entities, that will be augmented, by the provision of the new constitution, to 54 percent to provide a stable majority. This coalition will be mandated to appoint the prime minister and form a government. If, within a month, no such arrangement has been possible, there will be a run-off between the entities which came in first and second. Each will have a right to form new alliances. Those who passed the threshold in the first round will maintain their positions after the second round.

With the exception of the Dashnaktsutyun, which is currently in a coalition with the ruling Republican party, all others are in opposition and most of them have vowed not to enter a coalition with the ruling party under any circumstances after the April 2 election. If the ruling Republican party and the Dashnaktsutyun do not garner fifty percent plus – and they are not expected to unless there is outright manipulation of the vote — there will be a variety of different configuration possibilities to achieve a change of power.

In the run up to the elections, as the public speaks out, one can see a great deal of apathy and distrust towards the elections and what may follow. Pervasive and continuous electoral fraud and unfulfilled promises have left a deep scar in people’s psyche. Perhaps the promise of the new constitution will force a fair election and a just and legitimate government to heal the deep-seated wound and ease the pain.

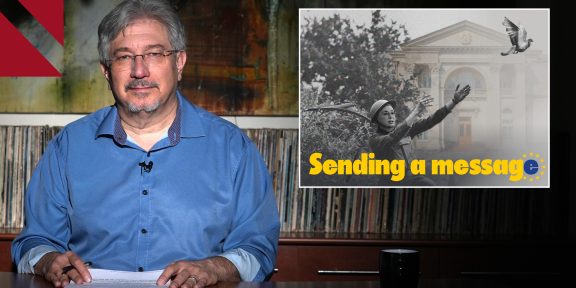

Armenia’s prime minister, Karen Karapetyan (pictured, in red jacket) leads the Republicans campaign although his name is not included in the party list. Republicans have announced that, if they win, Karapetyan will continue to lead the government. The big question is who will be the prime minister after Serzh Sargsyan’s second presidential term ends in 2018.