By Tigran Grigoryan

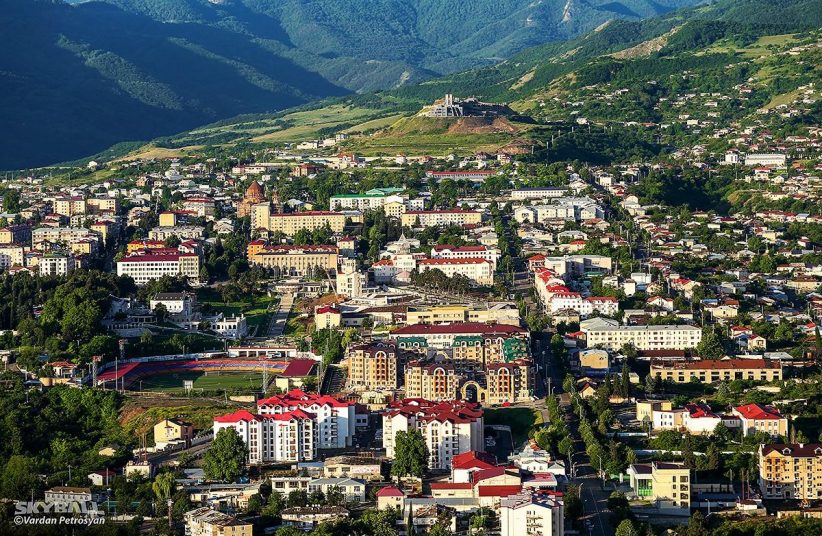

On June 6, the President of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic Arayik Harutyunyan and Armenia’s minister of territorial administration and infrastructures Suren Papikyan visited the southern part of the Kashatagh region of Artsakh. The aim of their visit was to discuss plans to build a new road that will connect Armenia’s Syunik region to the town of Hadrut in Nagorno-Karabakh. The road will pass through territories (Lachin, Qubatly, and Jebrayil) outside the former Nagorno Karabakh Autonomous Region (NKAO) and will become the third highway connecting the Republic of Armenia and Artsakh. The road is of crucial importance for the economic development of this underdeveloped part of Karabakh. It will lift hundreds of people out of poverty, creating economic opportunities for the emergence of self-sufficient households. Thousands of farmers will get opportunities to deliver their agricultural products to markets in Southern Armenia.

Azerbaijan has always expressed strong opposition to any kind of infrastructure project in the territories outside the former NKAO. Baku’s line claims that new infrastructure in these territories enhances the status quo and undermines the peace process. Oddly enough this view is shared by many foreign experts and journalists, who follow and cover the conflict. After the above-mentioned visit to the Kashatagh region, Thomas de Waal, a senior fellow at Carnegie Europe, tweeted that the decision to build the new road is highly controversial and will be seen as a provocative move.

This is not the first occasion when Thomas de Waal criticizes infrastructure projects in the territories surrounding the former NKAO. Back in 2017, answering a question about the reluctance of the OSCE Minsk Group co-chairs to condemn Azerbaijan’s aggressive actions on the line of contact, he noted: “You need 100 percent proof to blame one party in a conflict for an incident, and if you do so, people will also ask “Now what? So what is your sanction?” Besides, in its own quiet way, the Armenian side does things that also undermine the peace process, such as building of roads in the Kelbajar district or giving Azerbaijani settlements Armenian names.”

This is not just a textbook example of false equivalence but also a display of complete disregard for the basic needs of people, who have been living in dire conditions for decades. More than 17 thousand people reside in these territories. The vast majority are refugees from Azerbaijan, who were forcefully displaced from their homes after the outbreak of the Karabakh conflict. For many years they were mostly left to their own devices, both by the government and the international community. Being one of the prime victims of the conflict, they are denied even those opportunities which are enjoyed by the rest of the citizens of the NKR. No international organization operating in Nagorno-Karabakh is able to implement a project in these territories. In short, people living there are in isolation even by the standards of an isolated country. These facts are well documented in the International Crisis Group’s recent report on the Karabakh conflict.

The criticism of the attempts to alleviate the burden of people living in the territories outside the former NKAO is extremely hypocritical. It is crystally clear that there won’t be a negotiated solution to the Karabakh conflict in the near future due to a variety of reasons. This fact is widely acknowledged by the majority of experts and politicians.

So what are people like Thomas de Waal suggesting? Are they suggesting that the residents of these territories should live with non-existent infrastructure for decades to come, being condemned to systemic poverty? Or are they suggesting that these people, the majority of whom have already experienced displacement in their lifetime, should once again leave their homes?

For too long the existence and human rights of these people have been ignored. It is simply stunning that reputable experts and organizations, who portray themselves as champions of peace in the region, willingly oppose humanitarian projects which will create economic opportunities for one of the most vulnerable and underrepresented groups in the conflict zone.

And this is what’s wrong with this conflict. The majority of international actors are more bothered with Azerbaijan’s reaction than with the actual needs of people living in the conflict zone. That’s the main reason why Nagorno-Karabakh has been left alone in its fight against the pandemic. For the international community, NK is a disputed territory, a gray zone, a geopolitical headache. The rights and needs of people living in Artsakh are not even part of the conversation. If we want progress in the peace process, this attitude must change.

Tigran Grigoryan is a political analyst from Nagorno-Karabakh. He holds a Master’s degree in Conflict, Governance, and International Development from the University of East Anglia.